|

|

|

This

is taken from a magazine article which first appeared in Scottish

Field, in September 1973. |

Snaking

westwards, St. Vincent Crescent seen from its junction with

Corunna Street |

Catriona

Findlay

GLASGOW

has often been described as the

Victorian city; and certainly the compulsive building in that

period successfully wiped out most of the stone and mortar

evidence of its earlier Georgian prosperity - the latter a time

when it was noted as being "one of the most elegant towns in

Scotland".

Imagine, then, for a moment, that you are suspended above

Glasgow during, let us say, the first half of the 19th century;

suspended above a particular part of it, rather. What do you see?

The River Clyde still sprawling widely as it passes the quaysides

of the town, and meandering along the verges of the green fields

of Stobcross, adjacent to the village of Anderston still, at this

time, outwith the boundary of Glasgow; and from the village an

avenue of old trees leading for about half‑a‑mile to

the gates of Stobcross House which stands by the water. This house

is at the heart of the lands of Stobcross, which originally formed

part of the Bishop's Forest and later of the Great Western

|

|

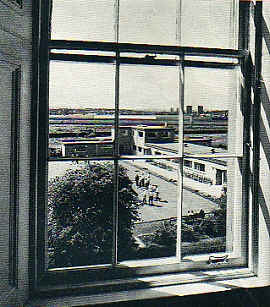

St Vincent

Crescent and the bowling greens, with the sheds of Queen's Dock

beyond and the fingers of multi-storey

flats south of the river

thrusting

against the horizon |

|

|

Common,

but which at some time, and some how, during the 17th century came

into the possession of the Anderson family who were for three

quarters of a century part of the ruling clique in Glasgow. In 1735 the Anderson family sold the estate to John Orr,

whose nephew 41 years later sold to David Watson, described as a

Merchant in Glasgow. The price was £3000 for 62 acres and the

mansion house.

In

1783 David Watson died, and his children's curators sold Stobcross

for £3750 to yet another "Merchant in Glasgow", John

Phillips, who lived in Stobcross

House until his death in 1829.

Some 15 years later Phillips' trustees sold the estate and

house for £58,246 to a syndicate headed by James Scott; who

with almost 20th century promptitude sold off 20 acres to the

Clyde Trust for about the same price as they had paid for the

whole. On this site the Queen's Dock was constructed, though

not until 1880.

Such

is the background to the part of Glasgow we are surveying from our

bird's eye position. But now the scene begins to change: on

this land in 1849 the Stobcross Estate Company began speculative

building, following what was the current fashion in London and

putting up tenements divided into flats, with communal pleasure

gardens - the first in Glasgow to be built in this style. The

architect was a Glasgow man, Alexander Kirkland; and for the

Company he designed a beautifully serpentine crescent of four to

ten roomed flats, three storeys high, that snaked along for almost

half-a-mile. |

|

From

a top floor window, looking to the bowling green |

|

"An

important, useful and ornamental addition to our city," one

writer described it. "The Stobcross lands," he continued,

"have now (1851) been laid out with streets, terraces, and

crescents, underlaid with splendid common sewers, which have no

connection with any other property, at an expense to the proprietors

of £7000. . . . Last year buildings to the value of more than

£30,000 were erected. . . ."

The

two acres in front of the principal crescent were laid out as

pleasure grounds "enclosed with a highly ornamental

railing" and even in 1973 part of the pleasure is still there,

for in St Vincent Crescent there are three bowling clubs along the

greater part of the frontage, with half-a-dozen greens among them;

but |

Tidying up of

a back green; the borders by the wall are bright with flowers |

|

the

old boating and curling ponds, which some of the oldest residents in

the area can remember, lost their "pleasure" aspect when

taken over by industry and a timber yard between the two World Wars.

St.

Vincent Crescent: the name itself did not please everyone. At

first it was called - appropriately, it would seem - Stobcross

Crescent. But, to quote the author of "Glasgow, Past and

Present", "a few weeks since some of the highly genteel

people who have the management of the matter, transmogrified

Stobcross into St. Vincent. What

these folks have to do with the island of that name in the West

Indies . . . .we do not

know; but we think they would have shown good taste in retaining the

name by which the locality was known in the days of their

fathers".

But

in spite of his criticism, the author was greatly in favour of the

actual development "for, combining the pleasures of a country

residence with the advantage of proximity to the city, and from the

liberal manner in which the grounds have been laid out, there is no

doubt that this will soon become a favourite location for a

desirable class of tenants".

Except for the matter of the grounds, that could well be true

even today.

The

"desirable class of tenants" who first moved into these

"fine, middle-class dwellings" paid rents ranging from

£40 to £70, and they tended to be people associated with the life

of the waterside harbour and port officials, sea captains and the

like. But the coming of the railway and the accompanying increase in

industrial development around the area put an end to the original

idea of extending the Stobcross building southwards to the river and

northwards to link with the fringes of the highly fashionable Park

area. What would have happened to St. Vincent Crescent itself makes

a good guess‑it might have snaked forever westwards.

Instead

it tended to come down in the world: slum landlords moved in,

multiple occupancy became a problem, neglect and consequent

deterioration of fabric ruined the visual delight of this sweeping

row with

its regular rhythm of tall windows with astragals, punctuated on the

ground floor by square pillared porticos. The main cause of the

deterioration was the zoning of land for commercial/industrial use -

something that always tends to doom residential areas near by, and

St. Vincent Crescent and adjacent streets were no exception to the

rule. The buildings, indeed, were scheduled, not for preservation as

might have been expected, but for demolition during the decade

1975-85.

|

Sunshine floods through the

windows of this first floor sitting room |

But

in the mid 1960s St. Vincent Crescent began to revive: the New

Glasgow Society office opened here, and into some of the flats moved

people who appreciated the place not just for its architectural

merit, but for some of the other qualities that the 19th century

writer had found so praiseworthy and which they felt could be

restored. In 1968, after considerable agitation by concerned

residents, Glasgow Corporation helped greatly by rezoning the area

and designating the foreground as permanent open space; the Health

Department has cooperated in reducing the nuisance of multiple

occupancies; the Parks Department has provided a garden and

playground; and in Lord Esher's report on "Conservation in

Glasgow", published in 1971, he made a special plea for the

preservation of the Crescent, already the subject of a preservation

order. |

| The

residents themselves do much to preserve and improve their

surroundings. The Crescent Area Association encourages a

co-operative scheme for painting all woodwork white on windows, for

restoring astragals wherever possible, for replacing iron railings

(only a few houses retained the original railings intact, but the

Association managed to acquire some two and a half tons of scrap

railings of the same pattern, and these are available for anyone who

can afford to erect them), and for tidying gardens and planting a

uniform hedging of privet along the length of the Crescent. Trees

have been planted in the pavement. Others have been planted by

Glasgow Tree Lovers Society; and the University is helping by

leasing ground in a common garden.

But

at the moment they are dealing with a greater threat than rundown

houses and gardens: the Electricity Board is planning to build its

head office for Glasgow north, plus a park for heavy lorries and

vans, adjacent to St. Vincent Crescent. The thought of 600 or so

people coming daily to work and parking their cars in the area is

understandably viewed with some misgiving by local residents and

they are appealing to the Secretary of State for some alteration of

the plans.

The

outcome is uncertain. Nevertheless the people who live here are

optimistic. And meanwhile there is always the consolation of lying

in bed on Sunday mornings watching the ore ships slip silently

past, or of listening in the night to the cheerful tooting of tugs,

or a much rarer pleasure nowadays of seeing 15‑20,000 tonners

riding floodlit on the high tide near the mammoth landmark of the

Stobcross Crane. |

|

|